Shin Kamen Rider: I expected to meet God and got a superhero movie instead

It was honestly a pretty good superhero movie, though

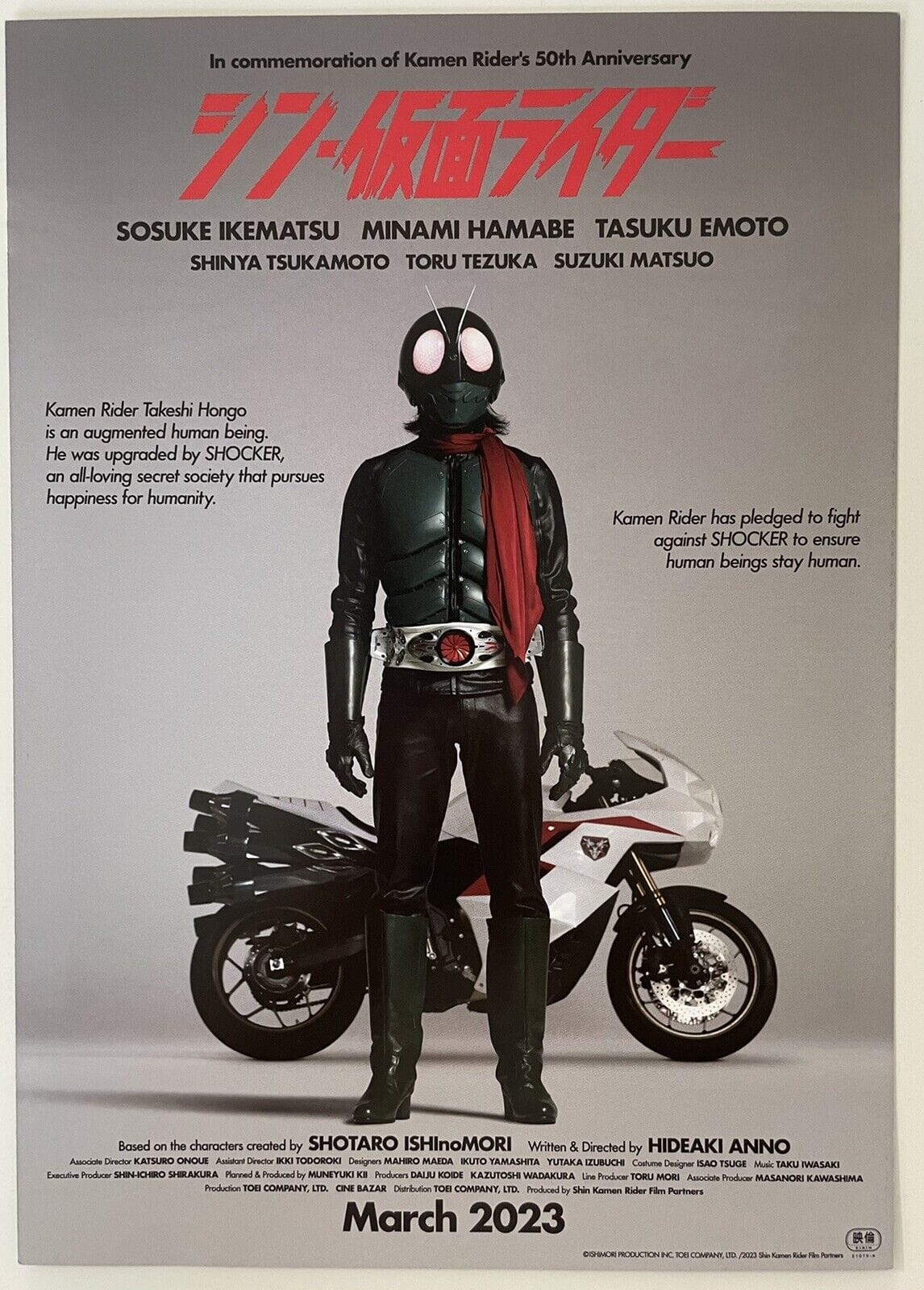

After Shinji Higuchi and Hideaki Anno’s Shin Godzilla and Shin Ultraman movies, I couldn’t possibly have had higher expectations for the conclusion of the “Shin” (New) trilogy of remakes, Shin Kamen Rider.

Godzilla was remodeled into a half-winking office farce that never diluted the threat and awe of the titular beast, but rather made it new and terrifying. The people were the joke, not the monster. Shin Ultraman plopped the titular cosmic hero into modern Japan, maintaining the original series’ bizarre situations and sense of childish wonder.

Both films were wildly entertaining experiences, and vivid reminders of exactly what we love so much about these titans of Japanese fantasy.

So for Hideaki Anno to take on Kamen Rider, his most beloved childhood superhero, was really exciting to me and every other fanboy. Given the standard that the Godzilla and Ultraman films set, I half expected to meet God during this movie.1

When Shin Kamen Rider turned to merely be a good movie— not a great one, but certainly a three-star— it hit like a real disappointment. Mostly, I was disappointed by the action: too much CG, not enough guys in suits punching each other in the quarry. But more importantly, there was no big, cathartic moment that left me in awe, the way Godzilla or Ultraman did.

But I was lucky enough to get to see the movie a second time, about a week later. Free of any pre-existing expectations, I was able to take in the movie on its own terms and accept it for what it was trying to do. I liked it a lot better that time.

Highly faithful, Highly Serious

Like the other Shin films, you can’t fault Shin Kamen Rider for unfaithfulness to the source material. Anno mixes elements from the 70s live-action show2 with Shotaro Ishinomori’s original manga while he moves things around a bit to make them his own.

The first Kamen Rider, Takeshi Hongo, is now slightly mopey and conflicted, with Dad issues, if that reminds you of anything Anno’s done. His assistant Ruriko Midorikawa is likewise re-imagined as a monotone dream girl; very reminiscent of Rei Ayanami, but not at all passive. As part of a concerted effort to tone down Kamen Rider’s fantasy to more believable real-world science fiction, their backers are now a black-ops unit of the Japanese government; their enemies are backed by a suicidal billionaire.

Hongo and Midorikawa’s battle against the evil syndicate Shocker plays out in chunks of the movie that feel like individual episodes, similarly to Shin Ultraman. Like the Kamen Rider TV show, they take down one of Shocker’s augmented minions at a time, and in the same order, too. Spider-Aug, Bat-Aug… you get the idea. Particularly in the earliest battles, Anno reshoots entire action sequences from the first episodes of the TV show. A cool visual from the very first episode— corpses breaking down into foam and disappearing— is used throughout the movie, to surprisingly powerful emotional effect.

The directorial style in the early part of the movie is probably the most fun Shin Kamen Rider gets. In its painstaking homage as experimental and fast-and-loose as the original series, shot continuity means nothing to Shin Kamen Rider. Characters simply appear in one place, and then smash cut to the next. Indeed, this becomes a punchline in the early part of the film. How did Kamen Rider get up that mountain? How did he get in front of that guy on his bike? The movie knows it’s doing this stuff, and it invites us to laugh along. It knows what Kamen Rider is, and it’s not ashamed of it.

“I can’t control how violent I become”

Despite Anno’s winking humor, the overall tone of the film is, in keeping with the original Kamen Rider, quite dark.3 The movie opens with a shocking bloodbath, our hero crushing the skulls of his opponents as stylized blood sprays out onto the trees.4 In the first minutes Hongo is forced to reflect on the bloodshed he’s caused and the unquestionable fact— we see his hands— that he’s become something other than human.

Indeed, the emotional core of this movie is characters finding their humanity in a world that is literally trying to take it away from them. Shocker’s goal in this movie is ultimately to harvest and fuse human souls into a group consciousness (yeah, another Eva touch), and over the course of the movie Hongo and Ruriko find themselves, find their resolve, and fight to reject Shocker’s nihilism. Pretty straightforward, as it ought to be.

I wanted more guys out at the quarry punching each other

This is a Japanese superhero movie, and it does deliver on guys in suits punching each other. Honestly, I thought this aspect of the film would be a little bit more traditional to the form. If you’re not very familiar with Kamen Rider or its descendants, this won’t matter at all to you, but it’s a very particular form: a bunch of guys in suits down at the quarry kicking the hell out of each other. It is art, dammit, and the guys in the quarry are unsung heroes.

Despite its embrace of the original’s style, Shin Kamen Rider wants viewers to see its violence as credibly real; hence that bloodbath at the start. So it doesn’t do much of its action in a traditional tokusatsu style— low-budget, high-effort action— which for me is a lot of the appeal of Kamen Rider in the first place. Its big action scenes are frequently done with the kind of CG you’re used to seeing in other modern-day Hollywood superhero films, with mixed results. The Cyclone bike’s CG transformations? Cool. Reducing the momentous fight between the two Kamen Riders to a hokey CG Dragon Ball impression? Awful.

There were rumors flying around after release that the action director walked from the movie because of Anno’s exacting demands, and after seeing the action in this movie I’m inclined to believe that maybe some of the reason there’s so much CG in this movie is that Anno wasn’t happy with what human beings were giving him.

A couple of action scenes flop— a (CG?) battle in a dark tunnel was so dark it actually wasn’t visible at one of the showings I attended— but the experiments mostly pay off. The battle against the Spider-Aug is deeply traditional; the fight with the Wasp-Aug is wild and experimental, chopping live-action footage into a high-speed cartoon reminiscent of Anno’s live-action Cutie Honey film. The final battle between the two Kamen Riders and, well, somebody else really powerfully expresses how outmatched our heroes were; it was the closest I got to awe.

Rider Jump! Rider Kick!

There are layers to the characters in Shin Kamen Rider, but not so much that their emotional turmoil takes over the standard hero narrative. By superhero standards, Takeshi’s trauma is trivial and easily conquered. By the end, the new Takeshi and Ruriko had really grown on me; I even got a little misty. Though the film is indeed a series of violent encounters with Shocker bosses, there are quiet moments where you see how much the characters have grown in a short time. Ruriko’s nature makes her intentionally “anime-cute”; it’s impossible for her not to grow on you.

All the “Shin” movies have left themselves open for sequels, but Shin Kamen Rider has a very explicit lead-in to the next adventure that strongly suggests one will be made. If that’s going down— and rumblings indicate that it is— you should probably look to Ishinomori’s manga for an idea of where the story will go.

So overall: I expected to meet God, but I got a superhero movie instead. And you know what? I’d take another one of these, with the caveat that maybe Anno should just let the action guys work this time. I mean, that definitely won’t happen, but I can ask for it.

Or at least be Thrillhouse playing Bonestorm. ↩

Which you can presently watch in its entirety on Tubi, should you choose ↩

Those first couple of episodes of the TV show are arguably horror-adjacent! The blood throughout the movie is probably homaged from the splatters in the second episode. ↩

A “PG-12” rating shows up at the beginning of the movie, so it’s apparent they couldn’t do full-on gore as in Black Suns, but still wanted to strongly express the brutality of super-powered combat. ↩