The ancient Elevator Action series immerses players into the world of elevators

Playing Taito games is cool

Immersion is an overused buzzword in video games, but that doesn’t make it meaningless. To the contrary, a game’s ability to interactively engage a player in its fictional world frequently makes the difference between a forgettable game and a memorable one.

And despite the monster computers that run our games today, immersion is not necessarily a matter of cutting-edge, photo-real visual fidelity, of the hairs on a character’s arm.

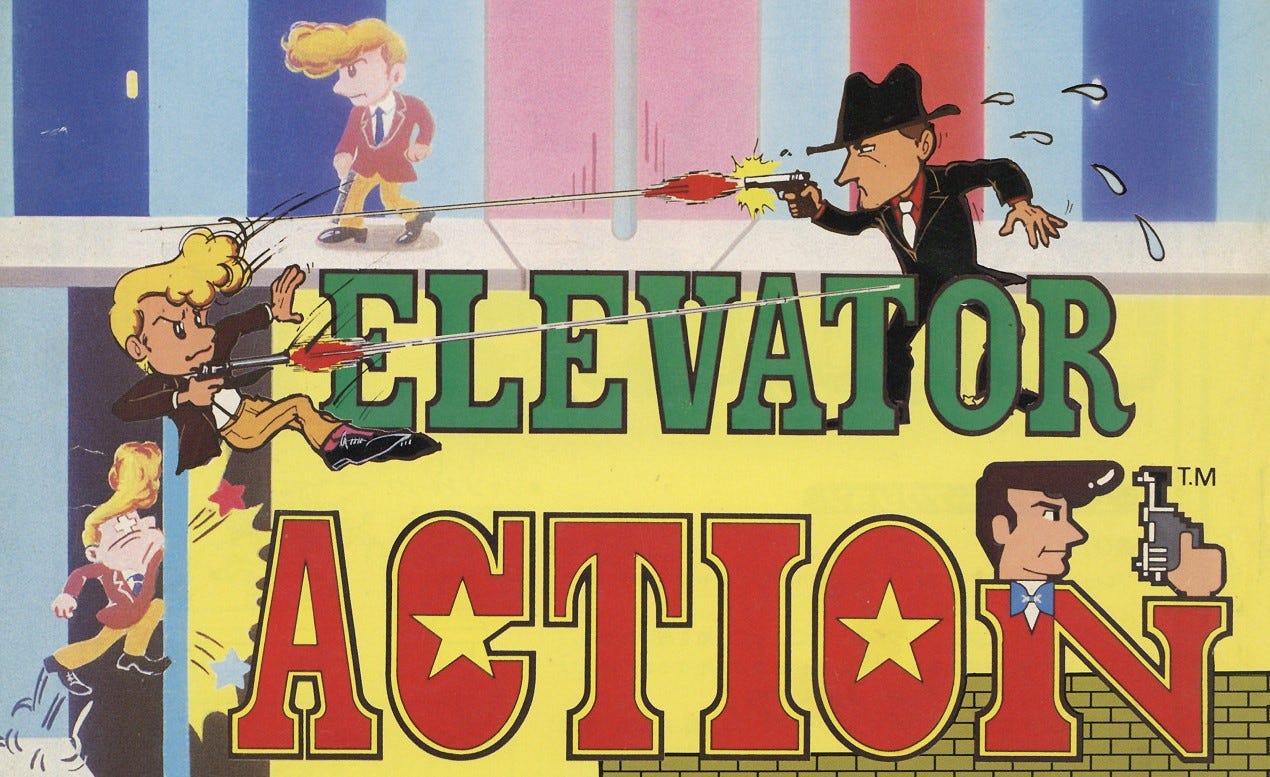

For an example, let’s go back to when games had a lot less to work with. 1983’s Elevator Action is a very directly descriptive title for a game with a spy-thriller theme. But it knows it’s about exactly that thing— players having shoot-outs on elevators, in a high-rise building— and it expresses this with as much creativity, detail and interactivity as its limited technology can muster.

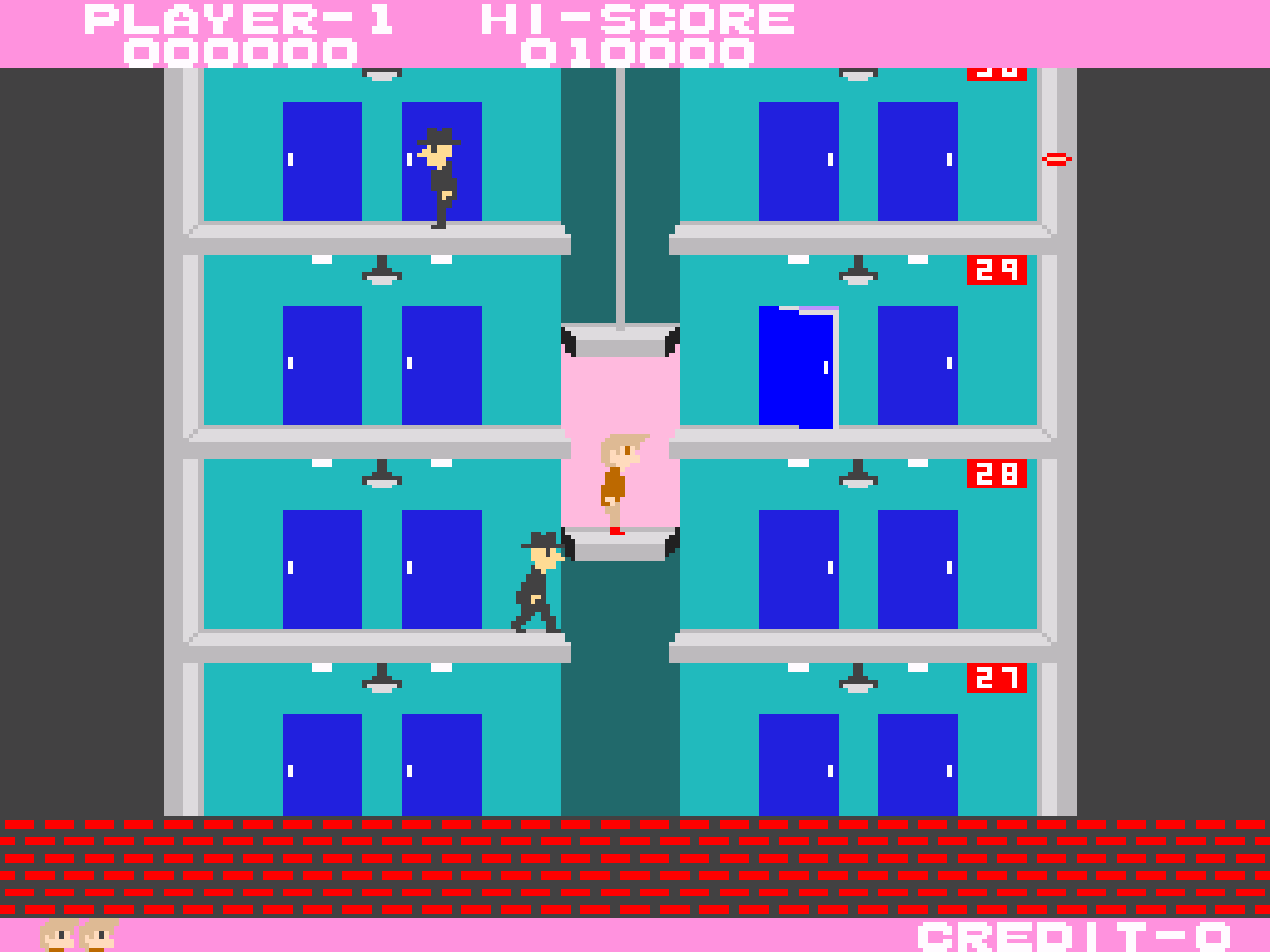

In case you’re not old, Elevator Action is a simple but strategic action game where the player is a spy slowly descending from the roof of a high-rise building via elevators and stairs, fighting with enemy spies and picking up data as they go. Escape, and the game starts over with slightly more and smarter enemy spies.

The thing that stuck out to me playing Elevator Action for the first time in many years was the ability to shoot out the lights.

Specifically, players can shoot any of the hanging ceiling lamps as they descend in the elevator. This calls for a pinpoint shot, at the very moment the elevator lines you up with the lamp. The lamp crashes straight down to the ground, and for a few moments the lights go out throughout the building. If you’re very lucky and time your shot very precisely, you can even kill enemies by dropping the lamp on their heads.

None of this makes any real-world sense, but as a game feature and a mode of immersion, it’s brilliant. Elevator Action takes a mundane detail of an ordinary place— something as relatable and boring as a hanging lamp— and makes it interactive and exciting, gives it nuance.

Everything in the Elevator Action building has some kind of interactive purpose, a weight, and a gameplay nuance. Take the elevators: obviously they move you around the building, but you’ll also use them to dodge and block enemy fire. You can even crush unfortunate enemy spies; or be crushed yourself, if you’re not careful. When you enter a red door to grab a file, you’re suddenly vulnerable as your character has to open and close it: you need to choose a safe moment to duck in and out or risk being killed as soon as you step out of the door.

These are all tiny details and easy to take for granted, but taken together they establish a strong sense of place by directly engaging the player with the environment. I was surprised at how just absorbed I got into Elevator Action’s tiptoe pace and methodical, strategic gameplay: it might be the game I’ve currently played the most on my Egret II Mini.

Now let’s look ten years down the line, at 1994’s Elevator Action Returns. The creators can do a lot more in terms of visuals and audio, and it’s all used in service of immersing the player into a gritty, violent anime world.1

There is a level of animation detail in Returns that is uncommon for 2D games: it’s hard, and nobody notices. But take a close look.

The character animation is detailed, but not flashy. Rather, a lot of hand-drawn attention has been lavished on their reactions to the game’s constant action-movie violence. Characters stagger, stumble and fall when shot, actually pushed back by the force of the bullet. Enemies tumble from ledges to their doom and flail as they’re immolated by grenades. It doesn’t just put you in the game world; the stylized animation immediately evokes gun-blazing Hollywood action, even subconsciously.

The environments in this game— a slum apartment complex, an airport, and more— are bustling and alive. Bullets ricochet off ceilings and leave behind smoke trails as they hit walls. Returns carries forth a little idea from Elevator Action— shooting out the lights— and populates all of its stages with destructible items. Security cameras, fire alarms, circuit switches; you might not even notice some of the things that you can blow up in this game until you drop a grenade on them.

The background items you’re working with are a little more generic and a little less evocative— wooden crates and explosive barrels litter the stages— but even more so than the original game, your survival depends on cleverly using the environment to your advantage against opponents with superior firepower.

Elevator Action Returns transcends the scale of the original game immediately by literally blowing up the first level, and the scale of its action gets bigger and bigger until you’re stopping a nuclear missile launch. But the cautious pace is the same. Returns forces you to slowly crawl through its stages, taking it all in as the atmospheric soundtrack scores your performance. The personality of this game is undeniable, and just like the original game, it’s the result of a whole lot of little details stacked together to create a larger illusion. That’s what the best do.

I’ve been playing these games on my Egret II Mini, but I realize that’s kind of an extravagant route. You can play Elevator Action on the Taito Milestones collection. Returns is significantly harder to come by, hence its status as a secret gem; you’ll need to resort to the 2000s Taito Legends collections, a rare Saturn port, or more likely, emulation. I, for one, don’t know anything about playing Returns all day on my 2006 MAMEcab.

This game’s aesthetic is frequently compared to late ‘80s and early ‘90s violent pulp anime OVAs like Gunsmith Cats and Cyber City Oedo; it really fits the vibe. ↩