What does Guilty Gear Strive Do Right?

NOTE TO ANYONE ON SOCIAL MEDIA WHO MAY READ THE HEADLINE, RATHER THAN THE ARTICLE: This is not a piece about one game being better than the other. Every time I turn on Xrd or XX— including for research on this piece, I come away saying “damn, what a good video game this is.” I really, really don’t care which game anybody wants me to say is objectively superior.

Nobody was sure about Guilty Gear Strive. I recall the very first beta that felt a bit like fighting in molasses, the unanimous outpouring of betrayed fan rage and concerned criticism. I recall developer Arc System Works saying hey, it’s a gamble, if it doesn’t work out we go back to Guilty Gear Xrd. I remember diehard fans hoping for that scenario.

So when Strive sold 500,000 copies— that’s not AAA, but it is about 10 times what the average game by this hardcore niche developer sells-- it was a big enough deal that Arc even let everyone know in-game. The game’s online population already made apparent that this game had done better than normal for Arc, but it was still a really pleasant surprise to see their gamble had paid off. And, I imagine, very vindicating.

It’s not the one currently played, but I believe Guilty Gear XX#Reload (pronounced “Sharp Reload”), the first expansion/balance patch for GGXX, is the game most representative of GG’s explosion onto the fighting game scene, the revolution of its systems. This game influenced Japanese fighting games for many years to come.

Guilty Gear is Arc’s flagship title, the fighting game for people who already love fighting games. Its aesthetic is heavy metal meets Shonen Jump. Its gameplay is unapologetically advanced, with high speed, a large degree of player freedom, and thus a steep learning curve. GG players love the game because of these elements, not despite them, so it’s particularly unsuited to the simplification trend of modern fighting games.

Indeed, the previous Guilty Gear Xrd modernized Guilty Gear XX with a light touch, slowing the game down only slightly and simplifying only its most arcane and technically demanding systems. Some players saw this as a betrayal, too: just not nearly as many. If you went any further than this, it was understood, it wouldn’t really be Guilty Gear anymore. It’d be a new game.

So Strive is a new game. It’s a radical attempt to make Guilty Gear more approachable by actually taking it apart, deliberately sacrificing much of its speed and complexity while still trying to maintain the core of what GG is. For a lot of players, Strive was a betrayal (as Xrd was perceived before it). But it did what it set out to do, which was reach a lot more players.

Putting aside play balance and without pitting the games against each other, I want to look at Strive and ask: what did it do right? We can’t cynically chalk its sales numbers up to only the animation. If we could, Xrd would have already sold half a million.

I’d argue that Strive achieves accessibility not so much by making things simple as it does by making them clear.

Complex systems, expressed loud and clear

Over the summer at Otakon, I came across a Guilty Gear Xrd setup and two May players who had clearly started on Strive and were playing Xrd for the first time. They were stumped.

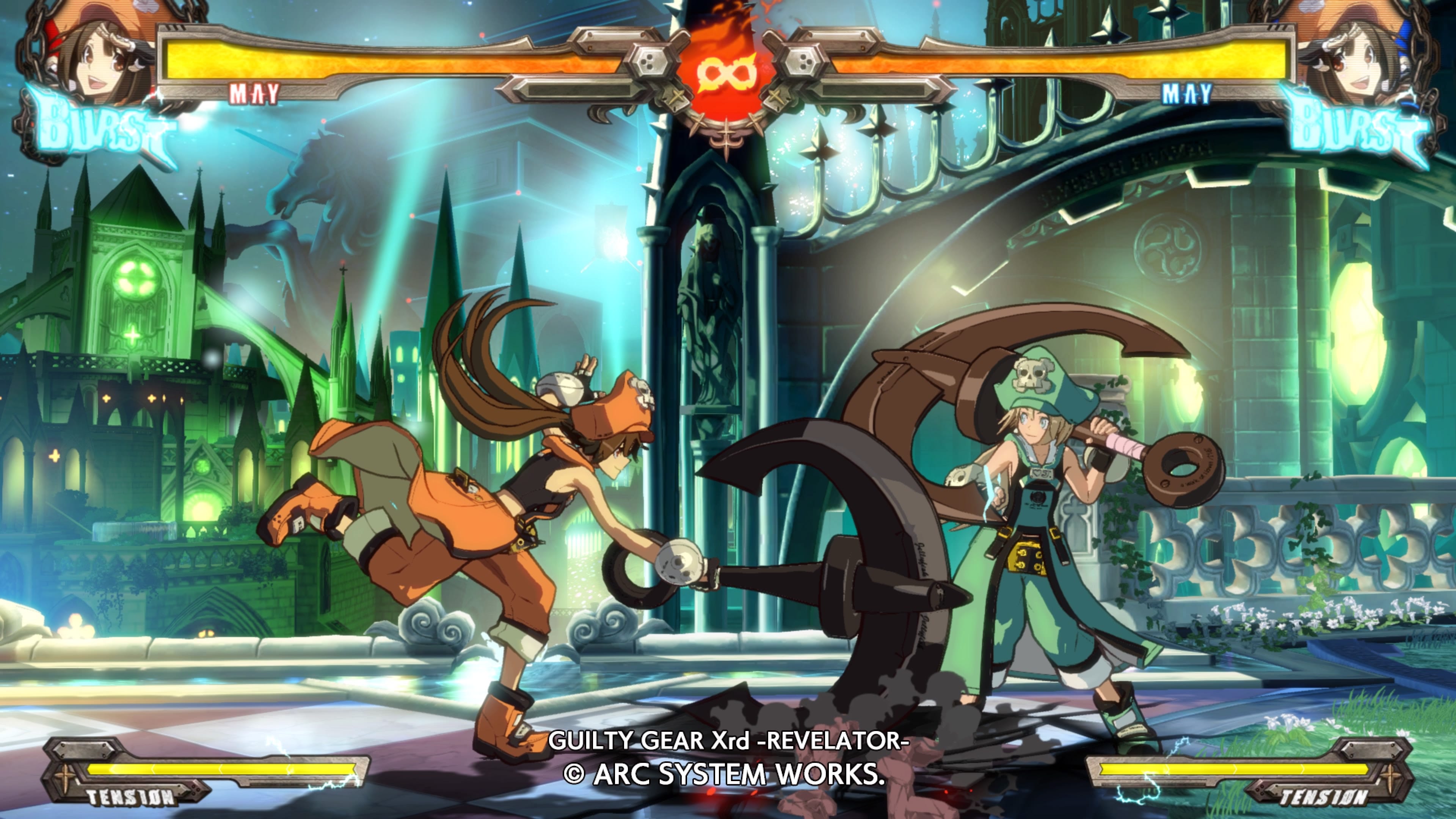

May has most of the same basic moves between Xrd and Strive. They were pressing all the same buttons, and seeing May throw her anchor around and ride on dolphins like they were used to… but they weren’t getting the same result.

Strive uses six buttons, more than previous entries. It retains many of the complex systems and rules that govern other titles in the series, like guard meter, tension, and burst. Players still have to input classical special commands (like “slide from down to right and press Punch”) to do their special moves. There’s tons of weird terminology like Dust attacks and Faultless Defense and Roman Cancels.

Strive didn’t simplify any of that. It simplified the moves themselves, and their effects. The attacks are powerful, and their effects are clear. The game has big, crunchy, obvious game-feel.

A new player does not have to know why Sol’s standing Slash punch or May’s standing Hi-Slash is so powerful— that has to do with animation frames and hitboxes— because the effects are so self-evident when that hit comes crashing in.

Sol can press Slash over and over again, and if the other player dares to try and counter-attack, they get punched in the gut for their trouble. This painful lesson in initiative is arguably one of the very first lessons players learn in Strive.

May’s buttons— like Hi-Slash— are fast, heavy, and safe: the anchor is weapon and shield. Most importantly, when she gets a big hit with Hi-Slash the whole world slows down, and a giant “COUNTER!” appears on the screen. Even if you never figure out what to do after this, you understand you’ve got a move worth using often.

From Potemkin’s Mega Fist to Sol’s Ground Viper, standard attacks and special moves alike have been tweaked to be very clearly powerful. It’s easier to find “the good moves” because they’re all good moves.

Combos and the damage baseline

Guilty Gear has always had masher-friendly controls. Hit Slash, then Hi-Slash, and do a special move. It doesn’t always work, but it’s easy enough to figure out on your own.

Ky Kiske combo exhibition in Xrd. One of the easier characters in Xrd. But Xrd is an order of magnitude more complex than Strive and as such, these combos are high technique from the start.

But part of the hardcore appeal of old Guilty Gear was that to achieve strong combo damage, you had to plunge deep into the game systems, discover how best to string attacks together, and then practice until you got it perfect. The accessibility problem was that these solutions were obscure unless you understood the game quite intimately. This wasn’t an accident, like say Marvel Vs. Capcom 2; it was the explicit design philosophy, and it hooked hardcore players who lived to put major effort into games.

Newbies could mash buttons, but they’d never figure out how to do significant damage, or even knock down the opponent properly. Meanwhile, learn a single basic (“bread and butter”, we like to say) combo, and you’d be dealing so much damage as to have an unbeatable advantage against anyone who didn’t.

There wasn’t a middle ground for damage, a baseline, and that creates a wider skill gap than is perhaps necessary. Strive puts forth that any player should at least be able to do okay damage.

Combos for one of the more straightforward characters, Giovanna. This of course gets advanced, but Gio is emblematic of the simplified Strive combo system.

In Strive at its simplest, you can press Slash twice and do a special move for a respectable combo with almost any character. You can do that in XX or Xrd as well, but it doesn’t work for everyone, and the damage is very low. The combo system remains deep, with plenty of room to squeeze out more damage and experiment with different moves. But with a higher baseline for damage— and high damage in general— the new player has more of a fighting chance, and feels a lot more powerful.

Likewise, by reducing the amount of moves that players can cancel into each other to only the most essential combo chains, Strive pushes players towards the combos that most experienced GG players already learned were the good ones a long time ago.

Slow motion

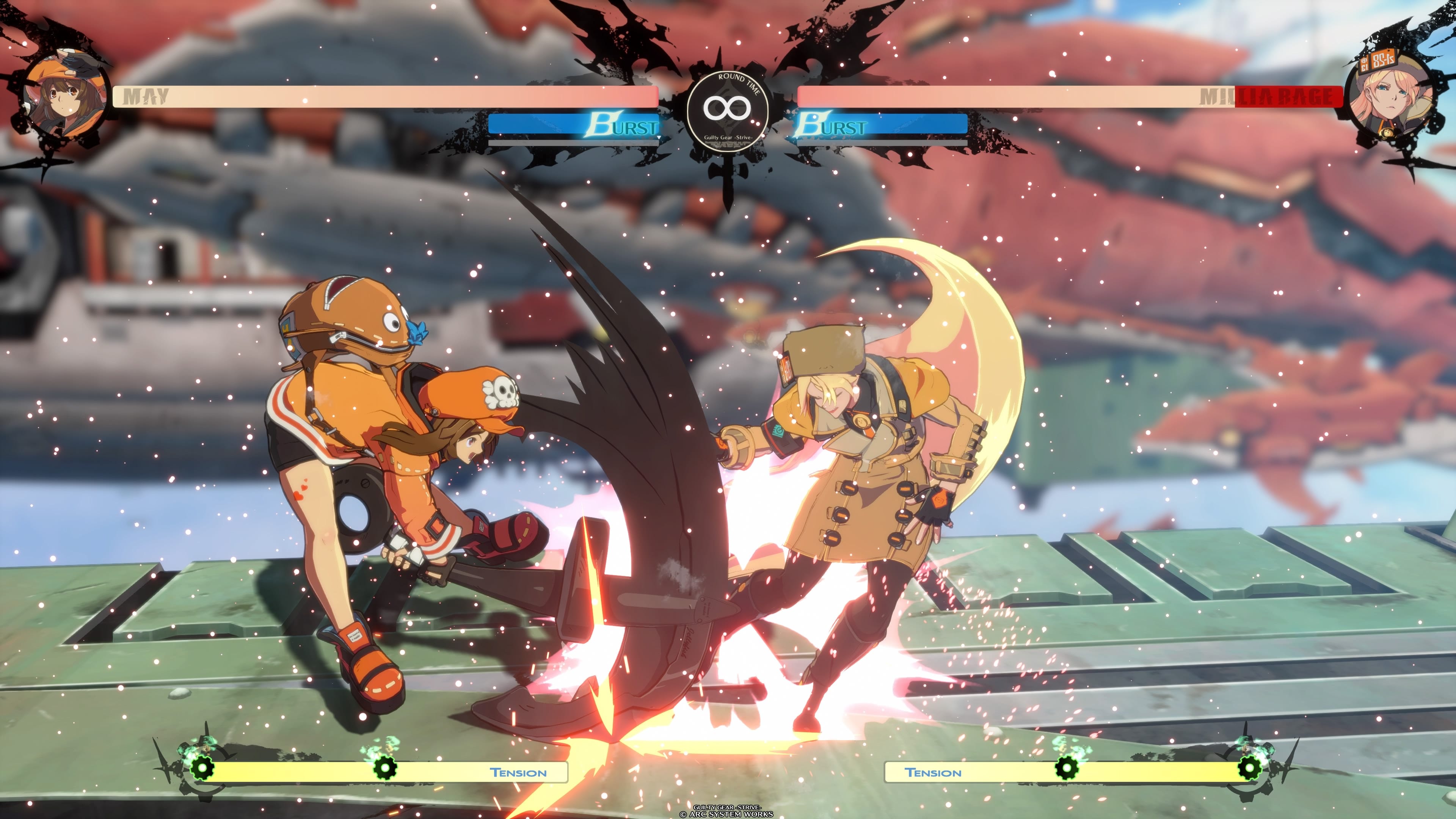

Part of the way Strive makes its action clear and readable is its extensive use of slowdown. Xrd introduced slow motion to the series to achieve the same goal, but Strive really runs with the concept.

(I admit this is an extreme case. Mushihime-sama in Ultra mode. Though this is an expert mode, there is no clearer visual explanation of how Cave slow-mo works.)

Let’s go outside of genre for a moment. In Cave’s classic shooting games, players weave a tiny spaceship through a seemingly impossible barrage of curtain fire. The secret to survival— and to these games’ appeal— is that the sheer amount of bullets onscreen (intentionally) slowed down the game’s humble hardware to a crawl. This gave cool-headed players time to plot a path through the bullet rain, and makes them feel like they’ve done something really amazing. And they have— but with a little help.

A supercut of counter hits in a Strive match.

Strive uses slowdown in the same way. When players land a big hit in Strive, the weight of the blow sends the opponent flying in slow motion, but the attacker can move freely. Not only does this deliver a powerful feeling of impact, it’s a clear sign to the player— start a combo now!

Traditional combo mechanics— including those of this game— involve instantly cancelling one move into another, often by performing a special move motion very quickly. The major counter gives any player all the time in the world to perform a combo.

The major counter is only one place where Strive uses slow motion and time distortion to make things easier. Regular counter hits and slams into the wall cause a more subtle slowdown effect, giving players ample time to confirm their hits and line up their next move. The mechanic helps everyone.

Corner play: breaking the wall

Getting stuck in the corner of the screen, unable to escape from the opponent’s attacks, has been a design issue in fighting games since Street Fighter II. Quickly, players learned to use it as a tactical advantage. Some fighting game characters specialize in getting opponents to the corner and never allowing them to leave. Xrd’s own Elphelt was a nightmare character, whose oppressive, nigh-unbreakable offensive pressure seems to have inspired many of the changes made to Strive.

A supercut of wall breaks in Strive.

Strive, controversially, transforms the corner into a breakable glass wall. You can still trap your opponent in the corner, but if you hit them enough while they’re there, you’ll eventually send them crashing through the “wall” of the screen into another stage. The fight resumes from the neutral middle of the new battleground, giving the defender a breather.

“But why would I ever want to let my opponent out of the corner?” is most of the objection from players who’ve been pushing the corner for 30 years. Strive has to bargain, offer an incentive. So when you knock your opponent through the wall, you get some extra damage, as well as a substantial amount of tension (GG’s “power” resource for super moves and other maneuvers) afterwards.

Positioning still matters. The pressure of the corner is still strong, and the attacker still has the advantage the whole time. But like GG’s Burst system, the goal is to insert a momentary breather into what might otherwise be a one-sided beatdown. You can’t keep a player from getting annihilated, but you can give them a “get out of jail free” card or two.

Depth for expert-level maneuvers

During the first beta of Strive— slower, floatier, restrictive— I thought, sure, this could be popular, but do I want to play it? And since that beta was a connectivity disaster, I didn’t really get the chance to play long enough to figure it out.

After some time with the final version of Strive, I felt very differently. The core play is much more straightforward, of course, but layers of competitive depth lie beneath. Every system that was designed first to make things easier for newcomers also has another facet for experts.

Nagoriyuki baits a counter hit and uses the slow-motion effect to move in for a barrage of heavy hits that deletes Jack-O’s life bar

Take, for example, slow motion. The major counter doesn’t just slow down the opponent for a newbie to get a grip on things; it gives the expert who already understands the mechanic extra time to confirm the hit and follow up with a stronger combo attack.

The Roman Cancel mechanic, GG’s trademark, has become even more versatile and multi-faceted in Strive. Starting out, you’ll use the red RC to continue combos, or to keep attacking after a blocked special move.

In this highlight at 30:39 (sorry, embed doesn’t work) Shine misses a Mega Fist and immediately corrects himself on landing with a purple Roman Cancel so that Hotashi’s Nagoriyuki can’t hit him while he lands. Hotashi is already in a stand Slash to catch Shine, but thanks to the RC Shine can now counter the standing slash with forward+Punch, so Hotashi RCs his intended punish and slides back to reset the situation. Two seconds of action. Deft movements all around.

But you can use a Roman Cancel to cancel any attack or movement at all, and Strive gives incentive to expert players who get creative with this system. The four different types of RCs allow players to squeeze more damage out of combos, fake opponents out, and slow time manually, among many other advanced uses. At high levels, the RC leads to some very tricky plays and takes a major role in the mind games players play against each other.

Tutorial by an erotic art enthusiast on not breaking the wall to maintain corner position.

Even the wall has its complexities: you don’t have to smash your opponent through the wall, and some players (especially I-No users) forgo the wall slam to keep the opponent cornered.

Strive’s “simplifications” have complex implications of their own, giving the game the long-term depth that any fighting game needs to keep players interested for months or years.

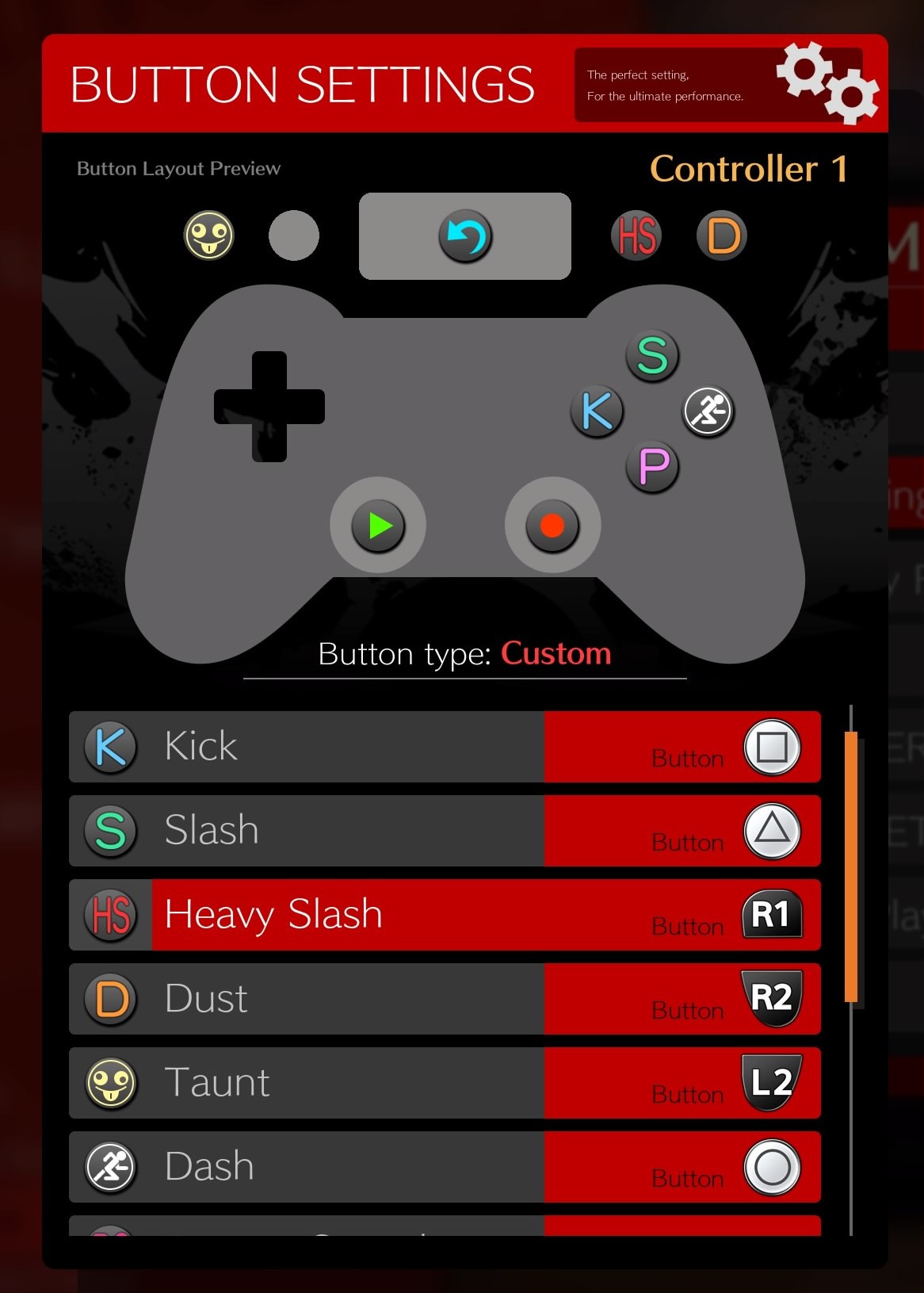

Matchmaking

No amount of “accessibility features” actually matter in a competitive game if you can only play against someone who’s way too good for you to beat. That’s what ranked play is supposed to be for: a system that evaluates your wins and losses and puts you up against players close to your level.

The goal is to give as many players as possible quality matches that they can enjoy and —in the best case— learn from and improve at the game.

I frequented the Guilty Gear Xrd lobby (as well as similar lobbies in other Arc games) and found it a cozy laid-back space. The problem was that while it was easy to get matches, it was tough to find players on my level to play serious matches against.

I was dominating and bored. It wasn’t that I was extremely good, I was just better than the people who challenged me in that room. If I wanted better matches, I had to hit Discord and private lobbies.

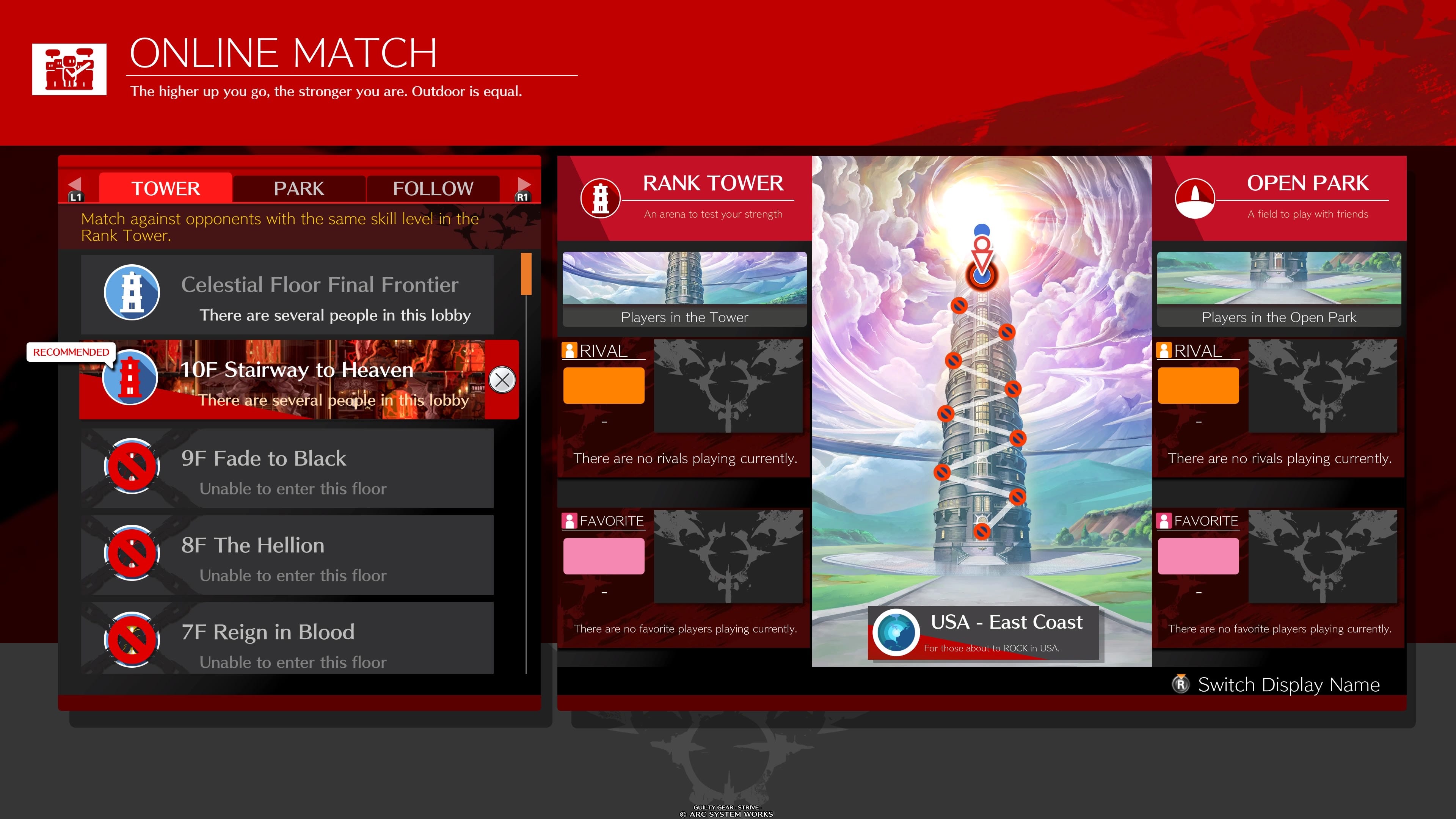

Enter Strive’s ranked tower. It’s controversial— not least because the lobby design itself is poor, and the connections are still buggy and weird— but I think the system is fundamentally good.

There are 10 tiers grouped by ability, starting from the very bottom. Floor 1 is for people who genuinely haven’t figured out how to play, and I must say, it’s extremely important to bring those players together so that they have fun rather than be mercilessly destroyed. No bullying weaker players, either: you can’t visit floors two or more ranks below your own.

The tower makes things better for high-level players like me by putting us in our own hard-earned “Celestial” lobby beyond the first 10 floors. It’s a difficult process to make it up there (win 5 out of 6 matches in Celestial: lose two and you’re out) and you have to renew your Celestial status every month. But the harsh requirements guarantee strong competition, which any competitive player craves.

In fact, the skill gap between Celestial and the main tower is so wide that players who make it into Celestial usually never go back. I certainly never did: the 10th floor is a bore by comparison. If you beat everybody you play in Celestial, on the other hand, it’s probably time to start entering tournaments.

On the other side of the coin, the isolation of the Celestial floor means that the strongest players online stay far, far away from the newbies or even the medium-level players. There is simply no need for us to waste each other’s time. In a genre where it’s literally the players’ job to frustrate each other, this is really important.

With the combination of superior rollback netcode (without which none of this ranking system would ever have worked) and a much wider player base than previous Guilty Gear entries, Strive has the most active online population the series has ever seen. A bigger player population is good for everyone.

Drawbacks

Strive makes enough trade-offs from the Guilty Gear X series that it’s just not Guilty Gear X anymore. Plenty of GG players understood perfectly well what Strive was doing, said “no, thanks”, and returned to GGXrd, GGXXAC+R, or some other game entirely. They’re not entitled; they just know what they like.

The core guessing game of Strive is now pretty strictly “Am I going to hit you or throw you?” versus old GG’s more varied types of offense. The game is heavily balanced towards rush-style point-blank offense, and outside of Roman Cancel tomfoolery, there’s often little room for subtlety or reason to go for anything but the biggest hit possible.

This is connected to accessibility: we’ve got characters so easy and so effective— like say May— that I feel like an idiot when I play any character who takes any work. (This is perhaps the Anji player’s lament. Please make Fujin good.)

In Closing: On the New Fighting Game

Strive is a genuinely new fighting game, and I think new games— with truly new ideas— are important to the genre, especially right now. Due to the severe demands of this genre in terms of polish and game balance, along with the generally conservative tastes of the target audience, it’s a lot easier to revisit and reiterate upon the many older game designs already out there than it is to create a completely new system.

The fighting game audience doesn’t reward radically new games: look at what happened with Street Fighter III. But if nobody takes a shot at genuinely advancing a genre— even if they fall flat on their faces!— it won’t ever move forward.

There was no guarantee for Strive. It could have been a huge bomb, alongside creator Daisuke Ishiwatari’s other big failures: Guilty Gear 2, the action-RTS, a game 100 years before its time, and Guilty Gear Isuka, an awkward attempt to force GGXX into a 2-on-2 team battle. But Arc went through with it anyway, even though it might have killed Guilty Gear for another ten years. It wasn’t going to be perfect. Not everybody was going to like it. And I’m glad it worked out.